Good old William Henry Harrison. If he’s remembered at all, it’s as the guy who was president for just a month before he died. But Harrison had a much larger effect on US history as governor of Indiana Territory than he did as president, and his territorial mansion is still standing in Vincennes, Indiana, open to the public. That mansion is known by the rather unappealing name of Grouseland (grouse is apparently a type of bird). The mansion is full of both prestigious historical artifacts and oddball art. It’s a frontier outpost that resembles an aristocratic Virginia plantation but has a bullet hole in the shutters and a lookout hatch on the roof.

I completely lucked into finding Harrison’s mansion on a road trip through Indiana, because Harrison was all over the place. He was born in Virginia, died in DC, and was buried in Ohio, yet his museum is in Indiana. He’d be a hard man to track down, that’s for sure.

The Harrison connection is one of the few claims to fame for the small town of Vincennes, so I spotted something truly incredible right away: a mail van with William Henry Harrison’s portrait on it. Where else are you going to see that?

Early 1800s Decorating + The Fortress Mansion of Grouseland

The first thing that struck me about Grouseland was that its exterior is easier on the eyes than its interior. The house recently had a multi-million dollar renovation, which involved decorating the interior with period-appropriate wallpaper and carpeting. Everyone on our tour agreed that it wasn’t what we would choose for our own homes, but red and green striped carpet must have been all the rage in 1806.

Another weird thing about Grouseland is that it doubled as a fortress. There are bars on the windows in the basement that are just wide enough to aim a rifle through. There’s also a door in the attic that used to open to the roof, which served as a lookout post. The door is still there on the inside, but the new roof doesn’t allow for it to open.

It’s a reminder that although this aristocrat from Virginia wanted a stately home, he had to be on guard in what was then the wild frontier. Harrison even let the townspeople of Vincennes stay at his mansion if they ever felt threatened by weather, Indian attack, or just needed a place to stay. Soldiers recuperated there, townspeople and orphans sheltered there, and Lewis and Clark even stopped by on their way home from exploring the Louisiana Purchase. Harrison was not just governor of Indiana Territory but also briefly the administrator of the vast Louisiana Purchase, meaning Lewis and Clark would have been just as eager to update Governor Harrison as they would President Jefferson.

What Did Our First “Old Man” President Really Look Like?

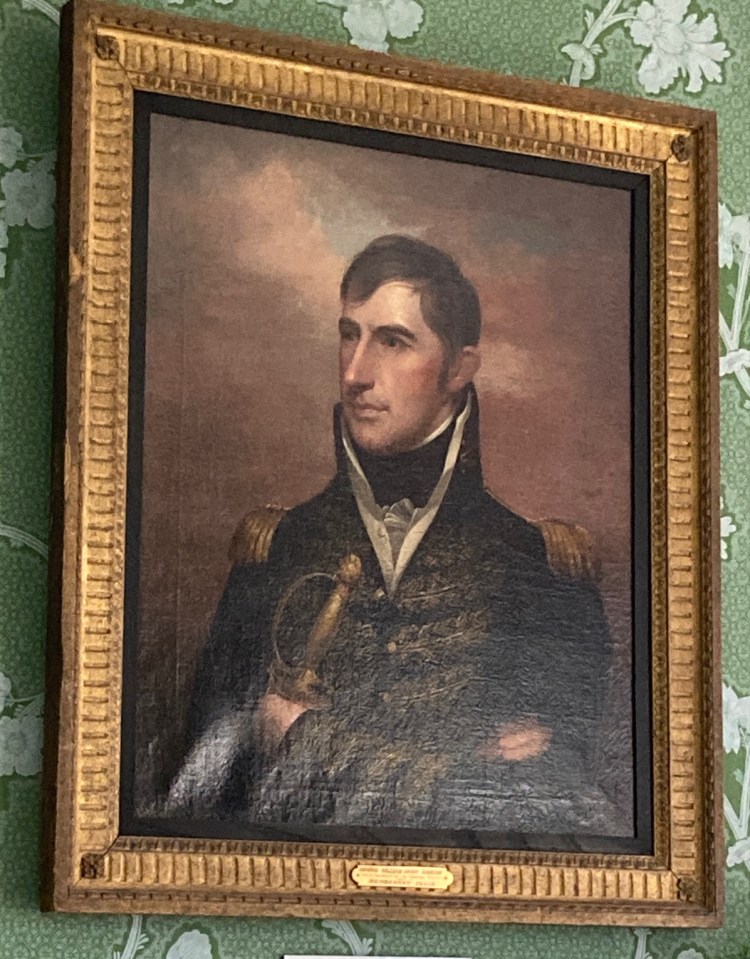

My favorite part of Grouseland was its collection of paintings and portraits. Some of them are famous, like this original painting of a young Harrison that I’ve seen in quite a few books and articles. The tour guide referred to it as “probably the most valuable thing in the whole house.” It used to show him in civilian clothes but was repainted after the Battle of Tippecanoe and War of 1812 to capitalize on Harrison’s fame as a soldier. How vain!

He looks very young in that painting, and all the others from this era, and it’s shocking just how early he gained power. He was in his twenties when he became governor and was still in his thirties at the Battle of Tippecanoe. He would have to wait decades for his shot to become president, by which point he was nearly 70.

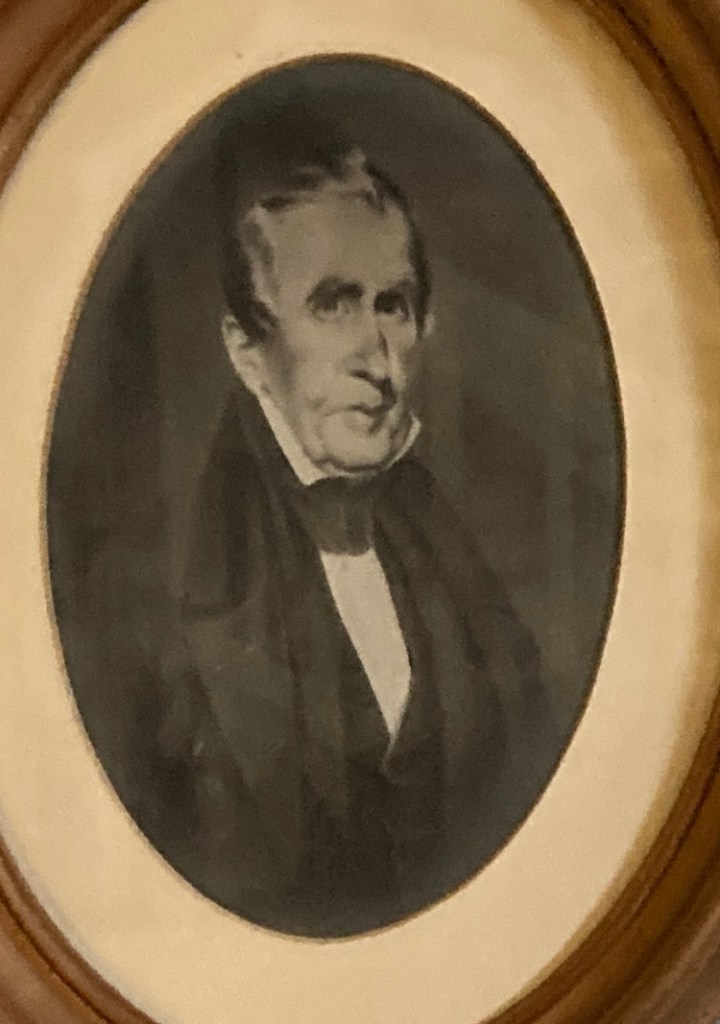

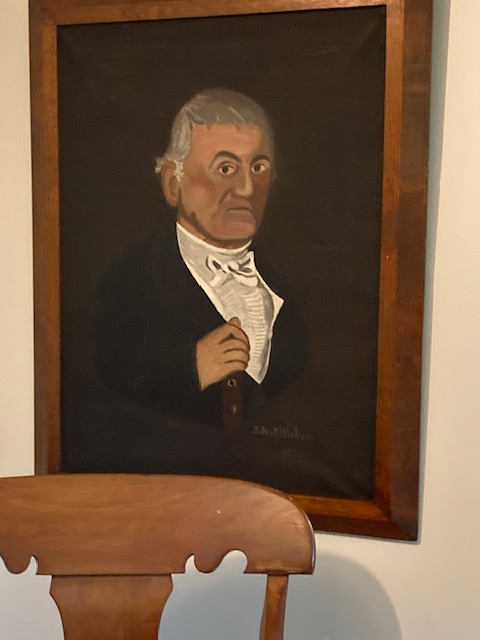

Because Harrison was our very first “old man” president, I was particularly interested in the above portrait of Harrison showing him noticeably older than all the others, even the ones from the 1840s. My suspicion is that some of his later portraits are touched up a bit, or at least de-emphasize his age somewhat. This is more like what I’d imagine a 68 year old to look like in this era, and Harrison was old even by presidential standards: the preceding eight presidents had all been 57-61 at the start of their terms. His opponents called him Old Granny.

The tour guide couldn’t remember who made this image, but said it must have been one of his final sittings and that it was a copy of an original that still existed. As far as my research could find, it seems to be a copy of this one from the Indiana Historical Society, which is almost identical. It may be the original that the guide was referring to.

William Henry Harrison is the final president we don’t have a photograph of. There is a famous painting of him that looks extremely realistic and was photographed using the Daguerreotype method, which is often mistaken for an actual photo of Harrison. It’s not. It’s a photo of a painting.

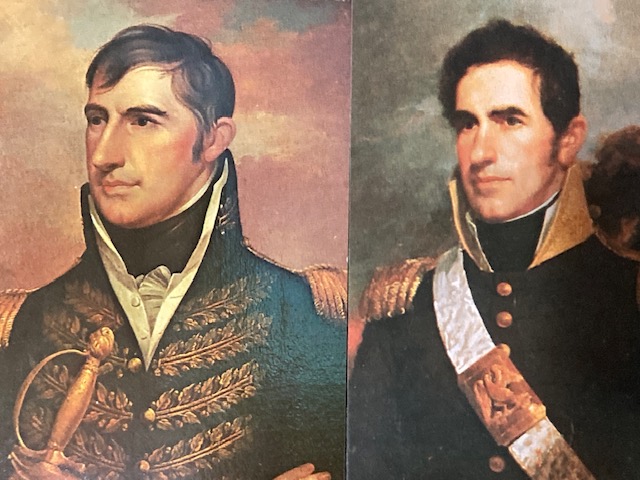

There are tons of paintings of Harrison, so we have a pretty good idea of what he looked like in real life, but each one has so many small variances that it left me wondering what the guy would have looked like in a photo. My wife noticed that his nose looks different in his famous war uniform painting, and it’s true – a slight bump on the bridge of his nose is gone, but it’s visible in other paintings.

And check out these two of young Harrison. One looks like Harrison and the other looks like he’s got some kind of “handsome” filter on. Artists sometimes took a lot of liberties with these things.

But as for what Harrison actually looked like as president? Most of his portraits as an old man look pretty similar, but I suspect the very best representation is the obscure portrait that shows him looking extra old. Whoever made it was not trying to be flattering by putting him in a uniform, changing the shape of his jaw or nose, or anything silly like that.

This was our first “old” chief executive, after all. A 68 year old president was really pushing it in 1841, and Harrison died just a month later. America wouldn’t dare to elect someone that old for another 140 years, when Reagan barely surpassed him at 69. These days, it seems like every president is older than the last, but back in his day, Harrison was the old one.

Artwork of Dubious Quality

A few of the portraits at Grouseland are, um, less professional looking. I don’t know anything about art or art history, so I’m not sure what you’d call these. Vernacular art? Early forms of outsider art? Maybe just amateur art? All I know is they made me smile.

This one is of Harrison in his glory days as a military hero and is a bit less impressive than the one above the mantle – not that I’d be able to do any better.

This rosy-cheeked fellow is apparently also William Henry Harrison, but I personally don’t see the resemblance.

Finally, this guy is Francis Vigo. “You can see how handsome he wasn’t,” our tour guide quipped. Do I see a little resemblance to that botched fresco restoration from Spain?

But come on, he couldn’t have really looked like that. An amateur artist did him dirty, right? Well…actually, that painter got closer to the truth than I realized. Here’s a more skilled portrait of the same man.

I still think the one at Grouseland looks like the botched Jesus fresco, though.

Which Presidents had the Best and Worst Handwriting?

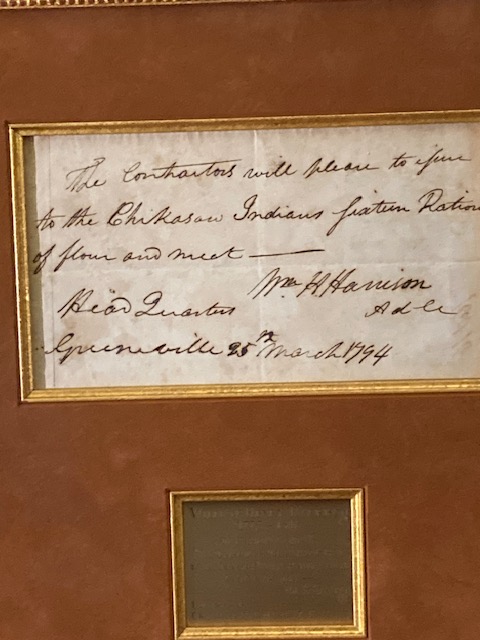

The most surprising thing about Grouseland is that they have authentic signatures of every president except the most recent two. A few impressions:

Millard Fillmore had excellent penmanship, which is unexpected, because he had to teach himself to read and had very little formal education. His teacher (and eventual wife) Abigail Powers got him caught up, and he would value education for the rest of his life. He and Abigail started the first White House library, and he once refused an honorary degree because he couldn’t read the Latin on it. What an absolute boss.

On the other hand, some of the most educated presidents, like Harrison, had unremarkable handwriting.

Ronald Reagan’s example was from the late 1980s and reminded me of the cramped, spidery handwriting of my paternal grandfather, who had Parkinson’s. It was very shaky.

Franklin Pierce’s looks like he just tried to get it over with as quickly as possible.

Zachary Taylor had a surprisingly nice signature. Old Rough and Ready often looked like he’d just rolled out of bed and was infamous for wearing wrinkled outfits and forgetting to comb his hair. He also had so little interest in politics that he never voted, not even for himself. I was surprised to see such a careful signature!

Some Dirty Secrets: Harrison Gets Censored

There were generous things about Harrison, like offering his home as shelter and founding Vincennes University. He was a longtime friend of Underground Railroad conductor George DeBaptiste, a free black man who became White House steward during Harrison’s brief presidency, although it’s unclear if Harrison knew about DeBaptiste’s work on the Railroad. However, Harrison had a darker side that the tour barely acknowledged. His role in getting chiefs to sign over their land rights was mentioned, but with an important detail left out: he would get them drunk first.

A scheming letter from Jefferson to Harrison also gleefully advises that it’s easier to deal with prominent Indians after getting them into debt. Harrison wasn’t a saint. His job was to grab as much land as possible by any means necessary, and he was good at it.

I also found it strange that there was no mention of Harrison being a slave owner who advocated for slavery’s expansion into the Indiana Territory. He was also known to sneak his slaves into free Indiana as “servants” who never gained their freedom. The guides are probably instructed to leave all this alone unless someone specifically asks about it, but that creates a vicious cycle: visitors won’t ask about it because they don’t know about it, and they won’t know about it if the tour doesn’t bring it up. It doesn’t mean we have to be proud of it.

(But wait, there’s more! Today, you get a super secret bonus scandal: Harrison reputedly had a bunch of children with one of his slaves. However, it hasn’t been proven that Harrison had a secret family, and we’ll have to see if genetic testing settles the matter some day. It’s reasonable for the tour to leave this out until it can be conclusively proven.)

Even when asked directly about some of these unsavory details, the guides might not give you a straight answer. For example, another visitor asked about Harrison’s slaves and was sidestepped with an anecdote about an instance when he refused one.

I mean, what’s the point of covering this up? You’re not going to ruin the great name of WHH, who has almost no reputation whatsoever. He is barely known to the general public except for dying faster than any other president. You’ll still be able to sell socks with his face on them.

Grouseland: Worth the Stop?

If you’re a hardcore history buff about the presidency or the American frontier, I would absolutely recommend stopping if you’re in the area. You’ll be treated to a ton of historical artifacts, a ridiculously large collection of presidential signatures, and an interesting, but unfortunately censored, view into Harrison’s world.

Subscribe for more history content: